Why We Forget Trips Faster Than We Think

Travel memories feel unforgettable in the moment, but our brains are built to compress, prioritize, and move on. Here’s the psychology behind why vacation details fade so quickly—and how to make them last.

Why We Forget Trips Faster Than We Think

Have you ever come home from a vacation and been surprised by how quickly the details started to fade? You might have sworn you'd never forget that stunning sunset on the beach or the little cafe you discovered in a hidden alley – yet weeks or months later, those memories seem hazy.

This experience is not just you; it's rooted in how human memory works. In this deep dive, we'll explore why travel memories fade faster than we expect, drawing on psychology research (for that academic credibility) and mixing in some relatable insights. We'll look at how our brains form and lose memories – covering everything from the classic forgetting curve and transience of memory, to the roles of attention, emotion, and context.

By understanding these factors, you can also learn how to make your precious trip memories last a bit longer. Let's unpack the science (in a non-boring way) of why we tend to forget our trips so fast, and what we can do about it.

The Science of Forgetting: Memory Decay and Transience

One fundamental reason we forget our trips quickly is simply that memory fades over time. Over a century ago, psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus pioneered memory research and described the forgetting curve – a graph showing how newly formed memories rapidly decline in the first days and weeks if we don't reinforce them en.wikipedia.org . In fact, humans tend to lose around half of their newly learned information within days unless they make an effort to review or rehearse it en.wikipedia.org . Travel experiences are no exception. Think of all the novel sights, sounds, and facts you take in during a trip – names of places, faces of people you met, bits of history from tours. Unless you revisit those details (by, say, writing in a journal or reminiscing about them), many will simply slip away in short order due to this natural memory decay.

Ebbinghaus’s classic forgetting curve illustrates how retention plummets shortly after learning. Without reinforcement, memories can halve within a day and continue to decline en.wikipedia.org . Our travel memories often follow this pattern if we don’t actively keep them alive.

Memory researchers classify this time-based fading as transience, one of the "seven sins of memory" identified by psychologist Daniel Schacter en.wikipedia.org . Transience refers to the deterioration of memory traces over time. Essentially, the mere passage of time causes stored memories to become less accessible or detailed en.wikipedia.org . When it comes to a vacation, the further in the past it is, the more likely we are to forget mundane aspects. Unless something about the trip was especially memorable or we make an effort to recall it, our brain lets the memory erode to make room for new information. This isn't a flaw in the system – it's how our minds stay efficient. We simply can't hold on to every detail of everything that ever happens to us, or our heads would be overcrowded with trivial data from years ago.

Research on forgetting shows that this loss isn't linear but rather exponential – a lot fades very quickly, and then the rate of forgetting slows down en.wikipedia.org . For example, you might vividly remember a special dinner you had on vacation the next day, but a month later only recall the “gist” (like I had a great meal in Italy), with the fine details (the appetizer, the server’s name, the exact decor) gone. Without some form of reinforcement or rehearsal, this rapid early decline in memory is almost inevitable. So, one reason we "forget trips faster than we think" is that we overestimate how much we'll remember simply with the passage of time. In the glow of the moment, we assume those wonderful scenes will be etched in our minds forever, but the hard truth of the forgetting curve says otherwise.

Attention and Encoding: Why Being Present Matters

Memory isn't just about time, however. It's also about how well we encode the experience in the first place. If you were half-distracted or not fully paying attention during parts of your trip, those moments will be encoded weakly – making them quicker to forget. In the modern travel era, a major culprit here is our beloved smartphone. Ever find yourself at a gorgeous overlook, but instead of soaking it in you’re fumbling with your phone camera, switching between video and photo, or scrolling through Instagram at dinner? If so, you’re not alone – and this habit can seriously impair how much of the trip you remember.

Psychologists talk about “attentional encoding” – basically, you remember what you truly pay attention to. Our brains have limited focus, and when that focus is split, memories suffer. Studies have shown that when we rely on technology to capture an event, we don't encode it as deeply ourselves. For example, in a museum study, participants who took photos of exhibits remembered fewer details than those who simply observed with their own eyes crimereads.com . The act of offloading the job to a camera made their brains say "no need to store this, the device has it." As one science writer quipped, our lazy brains figure the smartphone will remember for us, so we don't fully attend to the scene crimereads.com . On a trip, if you're constantly snapping pictures of every meal, monument, or sunset, you might inadvertently be paying less attention in the moment – and later you'll find the memory trace is thinner than expected.

It gets worse if you're preoccupied with your phone beyond just photos. A study published in the Journal of Travel Research found that heavy smartphone use on vacation impairs the vacation experience as an autobiographical memory crimereads.com . In plainer terms, people who stayed glued to their phones during a “trip of a lifetime” remembered far fewer details of the trip later on crimereads.com . Their attention was absorbed by the screen – checking messages, scrolling social media, or taking tons of pictures – so the brain wasn’t fully committing the actual surroundings and events to memory.

On the flip side, when you do force yourself to unplug and be present, the memories can imprint much more strongly. One travel writer recounted forgetting her camera on a boat safari in Uganda – at first she was upset not to be taking pictures, but later realized that because she spent the whole day truly observing everything, it became the most vividly remembered day of her trip psychologytoday.com psychologytoday.com . Freed from the "distancing effect of a screen," she soaked in the moments as they happened and later could recall them in rich detail psychologytoday.com psychologytoday.com . This story underlines a key point: attention is the gateway to memory. If we give more attention to our travel experiences as they unfold – being mindful and fully engaged – we create stronger memory traces. If our attention is divided or distracted, the experiences are more likely to slip away quickly.

It’s not just phones either. Even our own wandering thoughts can steal attention. Maybe you were physically at that beautiful waterfall, but mentally planning the next day's itinerary or worried about an email from work. Such absent-mindedness (another of Schacter’s "memory sins") means poor encoding in the moment, leading to patchy recall later. To truly remember a trip, we have to experience it, not just physically be there. This is easier said than done, but it’s a big factor in why some travel memories stick and others fade.

Emotional Salience: How Feelings Make Memories Stick (or Not)

Not all moments on a trip are created equal in memory. Think about a vacation you took a few years ago – you probably don’t recall every hotel lobby or taxi ride, but you do remember the highs and lows: that time your partner surprised you with a birthday cake, or when you got lost in a sketchy neighborhood and your heart was pounding. Emotionally charged moments (whether positive or negative) tend to lodge in our memory better than neutral ones. Psychologists call this emotional salience – the brain gives priority to events that evoke strong feelings.

There's an evolutionary logic to this. Our ancestors needed to remember life-or-death information (like where the lion attacked us or which berries made us sick) more than trivial details. In psychology this is known as the negativity bias: negative or threatening events often create deeper impressions than positive ones nationalgeographic.com . One research review famously put it as "Bad is stronger than good" in terms of impact on the mind nationalgeographic.com . On your trips, that means a travel nightmare – say, losing your passport or a frightening thunderstorm on your camping trip – might burn itself into memory (to be retold for years as the "travel horror story"), whereas the five uneventfully pleasant beach days blend together. Indeed, seasoned travelers often quip that "good trips come and go, but bad trips make the best stories." A National Geographic article noted that nothing is more forgettable than a journey that goes exactly as planned; it's the misadventures and challenges that we retell vividly nationalgeographic.com . When a trip tests you (missed connections, mishaps, etc.), it spikes stress and emotion, which can make those episodes more memorable – we encode them strongly because we felt them strongly.

However, there's a twist: negative moments might be memorable, but over time our mind has a way of softening their sting. Psychologists have observed a phenomenon called the fading affect bias – the tendency for negative memories to lose their emotional intensity faster than positive memories as time passes nationalgeographic.com . In other words, we eventually forget how bad the bad was, even if we still recall the incident happened. If you had a miserable cold during a trip, a year later you might remember that you were ill but not vividly recall the misery itself. Meanwhile, the positive moments from the trip may retain more of their warm glow. Our psyches seem to shed painful details and preserve the happier ones, a tendency that actually grows more pronounced as we age nationalgeographic.com (perhaps one reason nostalgia often paints the past as rosier than it really was).

So emotionally, our memories of a trip are constantly being reshaped: the sharp edges of stress dull over time, and the pleasant highlights might stand out in relief. The net effect is we might forget a lot of the nuance – especially the negative or mundane parts – and be left with a kind of rose-tinted summary. This can contribute to the feeling of "forgetting the trip" because what remains is a simplified story rather than a detailed account. You might recall “It was an amazing trip!” but struggle to explain why, aside from a couple of big moments.

Speaking of big moments, another theory in psychology that explains what we remember from experiences is the Peak-End Rule. According to this concept, people judge an experience largely based on two things: the most intense point (the peak, which could be either fantastic or terrible) and the ending of the experience. Our recollections tend to be shaped by those standout moments and how things wrapped up makingtradeoffs.substack.com . For travel, this means if your trip had one or two peak events – say, an incredible hot-air balloon ride at sunrise (peak positive) or losing your luggage for two days (peak negative) – those will form anchors in memory. Likewise, the way your vacation ended (a serene final day versus a hectic race to the airport) can disproportionately color your overall memory of the trip makingtradeoffs.substack.com . Everything in between, especially if it was routine, might fade faster because it didn’t trigger a strong emotional or evaluative response. We essentially compress the vacation into a story defined by its highlights.

So, one reason we forget trips quickly is that only the emotionally salient moments really stick, and they might be fewer than we think. The routine parts – the daily breakfasts, the countless beautiful buildings or landscapes that, while nice, didn't emotionally move us – those can slip away. Even positive experiences, if they are mild or repetitive, may not lodge firmly. Interestingly, a 2024 study found that while people initially remember positive experiences better right after they happen, those memories became more prone to forgetting after just 24 hours news.rice.edu . It suggests that positive moments feel memorable in the moment (you’re all excited about it that day), but unless they are truly remarkable, our brains may let many of them go in the following days. We often assume our emotional memories are ironclad, but research shows there's a trade-off: we retain the basic emotional gist (e.g. I had fun or that was scary), yet the details still fade if we don't reinforce them news.rice.edu . So even the joy and excitement of travel, if not tied to a peak moment, can be surprisingly fleeting in memory.

Context and Cues: "Out of Sight, Out of Mind"

Another subtle reason your trip memories fade faster than expected has to do with context. Memories are highly context-dependent – they are easier to recall when you’re in the same environment or situation as when they were formed simplypsychology.org . On your trip, you were surrounded by the cues of that place: the sounds, smells, language, the sight of the hotel lobby, the feel of the climate. All those contextual details were encoded alongside your experiences. Later, when you’re back home in a completely different environment, those original cues are missing. Psychologists call this context-dependent forgetting: when the recall situation is different, it can be harder to access the memory simplypsychology.org .

Have you ever noticed how memories come flooding back when you revisit a place? For instance, stepping off a train in a town you visited years ago might suddenly bring back a rush of recollections – a café on the corner you had forgotten about, a joke your friend made in the town square. That's context-dependent memory at work; the environment itself serves as a trigger for dormant memories. Conversely, when you are far removed from the travel context, you lack those triggers. “Out of sight, out of mind” – when you no longer see the coconut palms of that tropical island, you stop spontaneously remembering that breezy hammock nap you took under them.

In daily life after a trip, we’re bombarded with new contexts (home, work, everyday routines) that demand our attention and provide a completely different set of cues – none of which are related to our vacation. So, our travel memories end up tucked away, only to be pulled out when something prompts them (like flipping through photos, meeting someone from that destination, or returning to similar scenery). Without those prompts, retrieval failure can occur: the memory exists but you struggle to locate it because you don’t have the right cue simplypsychology.org simplypsychology.org . This contributes to the sense of forgetting. It’s not that the memory vanished entirely on day 10 after your trip, but it feels inaccessible when nothing around you reminds you of it.

Moreover, travel often involves many different places or rapid changes in context (different cities, hotels, etc.). While that makes the trip exciting, it can also cause memories to interfere with each other. Psychological interference is when memories overlap or blend, especially if they are similar simplypsychology.org simplypsychology.org . If you toured five churches in Europe, you might later mix up which one had the gilded altar versus the wooden one, or you might confuse events from two different beach vacations. Our long-term memory can get “confused or combined with other information during encoding,” as interference theory suggests simplypsychology.org . In the rush of experiences, details from Day 4 might be overwritten by similar details from Day 5 – a form of retroactive interference where newer memories (later in the trip) make it harder to retrieve earlier ones simplypsychology.org simplypsychology.org . Without careful differentiation (which requires attention and sometimes deliberate effort, like note-taking), a lot of a trip can become a blur of churches, museums, hikes, or meals that you recall in general but not specifically.

Finally, consider the role of routine and context loss after the trip. When traveling, every day is novel – which ironically can make it harder for the brain to store everything, because there's no familiar scaffold to attach the memories to. When you come home, you slip back into familiar routines that have their own strong memory patterns. These everyday habits and contexts can overwrite the fresh memories or at least bury them under the return to normalcy. Your Monday morning meeting at work might edge out the memory of that Monday morning you spent watching the sunrise over a volcano, simply because your brain now considers the meeting more immediately relevant.

In short, being away from the original context of your travels means you lose access to many natural cues for recollection, and the sheer novelty and volume of travel experiences can collide and jostle in your mind. Both factors make travel memories fade faster once you're back in everyday life.

The Gist vs. the Details: Our Brain’s “Compression” Algorithm

When we reflect on a past trip, we often recall the general outline – e.g., “We traveled down the coast, stopped at a beautiful lighthouse, then spent a few days in the city for a conference”. But if someone asks for specifics (Which restaurants did you eat at? What paintings did you see in the museum? What was the name of that tour guide?), you might draw a blank. This is because our memory tends to store the gist of experiences over the details. We form a coherent story of what happened and retain the meaningful core, but the finer points are prone to fading.

Cognitive research supports this phenomenon. In that Rice University study mentioned earlier, the psychologists noted that we focus on remembering the "big picture" of what happened rather than the small details news.rice.edu news.rice.edu . They found that even very memorable experiences for people – like universally significant events (a birthday party, a wedding, etc.) – are remembered for their central features, while peripheral details get forgotten over time news.rice.edu . In the context of travel, you might clearly recall the feeling of awe standing at the Grand Canyon’s rim (big picture) but forget what you had for lunch that day or even which lookout point you went to (details). Our brains do this as a kind of efficient compression: save the emotional and narrative essence, drop the rest.

Memory is also reconstructive. We don't store a perfect video of our trip in our heads; we store bits and pieces that we later reconstruct into a narrative. Each time you remember, you are actually rebuilding the memory from these pieces, and sometimes the pieces get weaker or lost. A National Geographic piece on travel memories pointed out that memory is not a static recording but a fluid, complex construction that “bends and flexes over time.” We don't so much retrieve a file as we reweave a story nationalgeographic.com . In doing so, our minds naturally fill gaps with logic or imagination, often without us realizing it. Over time, as details fade, the brain might stitch the memory together in a way that makes sense but isn't 100% accurate to how it went. This process can make some parts of the trip irretrievable or even replaced by general knowledge (e.g., you might "remember" the hotel room had a coffee maker because most do, though you no longer recall the actual room).

Another factor here is that not all details are created equal – some simply don't stick because they weren't meaningful to us. Memory researchers Morales-Calva and Leal note that our brains must do “selective forgetting for information that isn’t as important,” essentially pruning away trivial details so we can focus on what matters news.rice.edu news.rice.edu . During a trip, you are inundated with sensory information and experiences. Your memory system has to decide what is important enough to keep. Emotional resonance, as we discussed, is one criterion. Another is personal relevance: did this detail matter to you? If not, it’s a candidate for quick forgetting.

So when you think back on a trip and feel like you've forgotten a lot, it might be that you’ve kept the essential story and let the smaller stuff go. You remember that you went hiking and it was beautiful, but you forget how many miles or what brand of hiking boots you wore. You remember the laughter at a funny incident, but forget the exact joke. This is normal – our memory favors meaning over minutiae. The surprising part is often that we thought we would remember those little things (because in the moment they seemed noteworthy or we simply took memory for granted), and later we're confronted with blank spots.

There’s also a bit of overconfidence in our memory at play. During an experience, especially a happy one, we might internally say, "I'll never forget this!" The sunset was that gorgeous, the meal that delicious – surely unforgettable. But research on memory shows that people often overestimate how well they will recall something later (a kind of metamemory illusion). We don't anticipate the steep drop-off of the forgetting curve, or the fact that our brain might decide that detail wasn’t essential to keep. Thus, we are caught off guard when just a short time later we struggle to remember. We think our memories are more durable than they truly are.

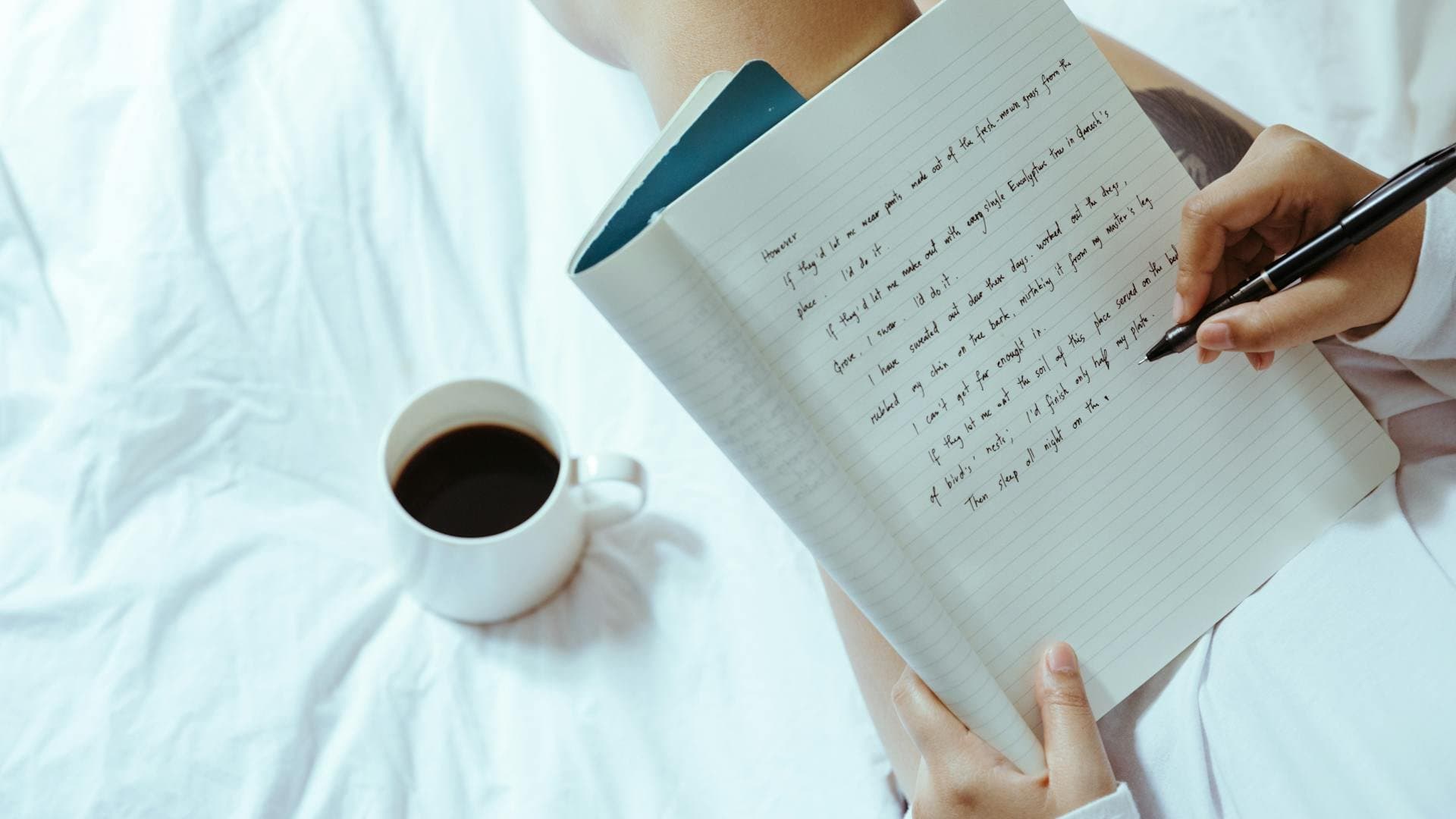

Your trips deservemore than a camera roll

How to Make Travel Memories Last (Tips from Science and Experience)

All this might sound a bit doom-and-gloom – are our treasured travel memories doomed to fade into oblivion? Not necessarily. Understanding why we forget so easily also illuminates how we can remember better. Here are a few research-backed (and common-sense) strategies to help your trips stick in your mind longer:

-

Be Mindfully Present: As much as possible, engage fully with the moment during your travels. Put down the phone sometimes and really absorb your surroundings. The more attention you give an experience, the stronger its encoding in memory crimereads.com . Some travelers intentionally plan “camera-free” time or take mental snapshots – focusing on each sense (sights, sounds, smells) – to form richer memories. Mindfulness isn’t just feel-good jargon; studies have shown it can improve memory retention by reducing distraction. Treat moments on your trip like you need to remember them, and you probably will remember them better.

-

Choose Emotional and Novel Experiences: You don’t have complete control over what will feel meaningful on a trip, but you can aim to include experiences that are likely to spark emotion or awe. These will naturally become anchor memories. Travel planner experts often suggest incorporating a “peak” experience (a bucket-list activity or something you’re very excited about) and a satisfying finale to leverage the Peak-End Rule makingtradeoffs.substack.com makingtradeoffs.substack.com . While you can’t make every minute deeply emotional, make sure you have a few truly memorable moments in the itinerary. And when the challenging or unexpected happens, remember it’s likely to be a memorable story later – embrace it (safely, of course)!

-

Get Some Rest and Reflection: It’s tempting to go hard and see everything, especially on short trips, but cramming experiences nonstop can backfire for memory. Our brains consolidate memories during periods of rest and sleep magazine.hms.harvard.edu . That’s when short-term impressions turn into more stable long-term memories, and the brain literally decides what to keep or discard from the day magazine.hms.harvard.edu . If you’re sleep-deprived or always on the go, consolidation may suffer. Try to get good sleep on your trip (I know, jet lag and red-eye flights make this hard!) and consider taking short breaks to mentally recap what you’ve done. Even a quiet 15 minutes journaling in the evening or chatting about the day’s highlights with your travel companion can help solidify those memories. Spacing out your experiences a bit, rather than a constant blur, gives your memory a chance to catch up.

-

Document Wisely (Photos, Journals, Souvenirs): There’s a balance to strike with documentation. As noted, taking hundreds of photos you never look at again won’t help you remember – and might actually impair your initial encoding crimereads.com . However, reviewing photos afterward can serve as great context cues to reactivate memories. So by all means snap some pictures of meaningful moments, but don't let the act of photography dominate the experience. Perhaps keep a travel journal or voice notes – writing about what you saw and felt is an excellent rehearsal that boosts memory (plus you capture details while fresh). Some travelers keep tickets, receipts, or little souvenirs; these tangible items can later jolt your recall (“Oh, that train ticket – I remember the beautiful scenery on that ride now!”). The key is to use these tools to reflect, not just collect. A study in Psychological Science found that taking a moment to describe an object or experience in your own words can improve memory for it, compared to just passively looking psychologytoday.com . So, consider jotting down a few notes about each day or telling your friends a story or two when you get back – recounting the trip can reinforce those neural pathways.

-

Revisit and Reminisce: Don’t just stash away your travel in a mental vault upon return. In the weeks and months after, revisit your memories periodically. This could mean making a photo album and paging through it, or having a reunion with travel buddies to reminisce. Each time you actively recall the trip, you are practicing retrieval and thus keeping the memory alive (this is akin to spaced repetition, a known strategy to combat forgetting nesslabs.com ). Even years later, deliberately reminiscing – perhaps on the anniversary of the trip or when something reminds you of it – can help maintain some of the detail. Reminiscing isn't living in the past; it's recharging the memory so it decays more slowly.

-

Embrace the Story Over Facts: Finally, accept that you won’t remember everything, and that’s okay. Focus on the story you can tell and the feelings you retain. Our identities are built on these stories crimereads.com crimereads.com – why we travel, what we learned, how it changed us. If the small stuff fades but you still carry the inspiration or joy of the journey, then its impact hasn’t been lost. And for the things you truly never want to forget (maybe a profound conversation with a local or the way a landscape looked at a precise moment), consider actively preserving them through creative means – write a blog, make a video montage, paint a picture, anything that forces you to engage deeply with the memory while it’s fresh.

In conclusion, we forget trips faster than we'd like largely because our brains are designed to prioritize, simplify, and move on. Memory fades with time (transience), it drops the non-essentials (gist-over-detail), it needs our attention to stick (encoding effects), and it depends on context cues that we often lose once we're home. Add to that the sheer flood of new stimuli during travel and our tendency to jump into planning the next adventure, and it’s no wonder those vacation days start to blur. But by understanding the science of memory, we can also hack our travel experiences a bit – savoring the moments as they happen and revisiting them afterward – to stretch out those memories. Your trips are part of your life story, and with a little effort, the best of those stories will stay with you. As memory researchers like to say, we remember what we make important – so make your travel experiences important in how you engage with them, and you’ll find you remember them longer, richer, and more vividly.

Questions

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why do we forget trips so quickly after coming home?

We forget trips quickly because memory naturally fades over time, especially when experiences aren’t revisited or reinforced. Once we return to daily routines, the brain deprioritises travel memories in favour of new, relevant information. Without reminders like reflection, storytelling, or photos, details are lost rapidly due to normal memory decay.

- Is it normal to forget details from an amazing vacation?

Yes — it’s completely normal. Even emotionally positive experiences are subject to forgetting. Research shows we often retain the feeling of a trip (that it was great) while losing specific details like places, conversations, or timelines. The brain stores the “gist” of experiences rather than every detail.

- Do photos and videos actually help us remember trips better?

They can — but only if you revisit them. Taking lots of photos without later reflection can reduce how deeply memories are encoded. However, reviewing photos, creating albums, or writing captions can trigger context-dependent recall and significantly improve long-term memory of a trip.

- Does using your phone too much on holiday affect memory?

Yes. Studies show that heavy smartphone use during travel — especially constant photography or social media scrolling — can reduce how much you remember later. Divided attention weakens memory encoding, meaning the brain stores fewer details from the experience.

- Why do bad travel moments feel more memorable than good ones?

Negative or stressful events create stronger emotional responses, which makes them easier to remember. This is known as negativity bias. However, over time, the emotional intensity of negative memories tends to fade faster than positive ones, which is why trips often feel better in hindsight than they did at the time.

- Why do travel memories come back when you revisit a place?

This happens because memory is context-dependent. Being in the same environment — or seeing similar sights, smells, or sounds — acts as a powerful retrieval cue. When you return home, those cues disappear, making memories harder to access until they’re triggered again.

- How can I make my travel memories last longer?

To remember trips better, focus on being present, reduce distractions, reflect regularly, and revisit memories after the trip. Journaling, storytelling, reviewing photos, and even talking about the trip with others help reinforce memories and slow down forgetting.

- Is forgetting trips a sign of poor memory?

Not at all. Forgetting travel details is a normal part of how human memory works. The brain is designed to prioritise meaning over detail and relevance over nostalgia. Forgetting doesn’t mean the experience lacked value — it means the brain has efficiently compressed it.

Sources:

-

Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve research on how quickly memories decay en.wikipedia.org.

-

The Seven Sins of Memory – transience as a basic memory “failure” over time en.wikipedia.org.

-

Psychology Today – anecdote on experiencing a safari without a camera, and research showing taking photos can impair memory of events psychologytoday.com crimereads.com.

-

Study in Journal of Travel Research – smartphone distraction leading to weaker vacation memories crimereads.com.

-

National Geographic – why “bad trips” (negative events) are memorable; negativity bias and fading affect bias in memories nationalgeographic.com nationalgeographic.com nationalgeographic.com.

-

Rice University News (2024) – evidence that positive experiences can be quickly forgotten and that we remember the gist while details slip away news.rice.edu news.rice.edu.

-

SimplyPsychology – context-dependent memory (better recall in the same context) and interference theory (memories overlapping) simplypsychology.org simplypsychology.org.

-

Harvard Medical School – role of sleep in memory consolidation (brain filtering what to keep from daily experiences) magazine.hms.harvard.edu.

-

Julia & Thomas Berolzheimer, Tradeoffs blog – applying Peak-End theory to travel planning for lasting memories makingtradeoffs.substack.com makingtradeoffs.substack.com.

-

CrimeReads – discussion of technology’s effect on memory and outsourcing memory to devices crimereads.com (Andrea Bartz).

-

National Geographic – memory as a reconstructive process that we reshape over time nationalgeographic.com.

-

SimplyPsychology – general theories of forgetting, including lack of consolidation and retrieval cue issues simplypsychology.org simplypsychology.org.

Related reading:

- How Travel Memories Work: The Science

- The Complete Guide to Travel Journaling

- The Psychology of Travel Nostalgia

Fight the forgetting curve. TripMemo helps you document trips while details are fresh—before your brain deletes them.

%20copy%202.webp&w=384&q=75)

%20copy%203.webp&w=384&q=75)